When the American writer and diplomat Washington Irving was staying at Granada's crumbling Alhambra in 1829, he one day came across a 'turbaned Moor' sitting by a fountain in the Court of Lions at the heart of the palace complex. The man, Irving discovered, was an immigrant from Tetuan, in Morocco, who sold rhubarb, trinkets and perfume in a shop in the centre of Granada. As they fell into conversation, the Moor told him he often visited the Alhambra to indulge his nostalgia for the past wonders of Islamic Spain.

'Ah senor,' he said, 'when the Moors held Granada they were a gayer people than they are nowadays! They thought only of love, of music and poetry. They made stanzas on every occasion and set them all to music. He who could make the best verses and she who had the most tuneful voice might be sure of favour and preferment. In those days, if anyone asked for bread, the reply was "make me a couplet", and the poorest beggar, if he begged in rhyme, would often be rewarded in gold.'

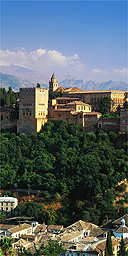

The Court of the Lions remains the centrepiece of the Alhambra, a pleasure palace for the Nasrids, the last Muslim dynasty to rule Granada until they were finally expelled in 1492 by the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella. The court is a symbolic representation of paradise divided into four parts separated by rivulets meeting in a central fountain. Today, the court looks little different from the way it was in Irving's day, a tribute to the technical genius of the fourteenth-century Muslim engineers who constructed the reservoirs and waterways that fed the palace.

Around the lions of the fountain, a melancholy poem in Arabic script is meant as a celebration of the brilliance of the craftsmen who built it, but also expresses intimations of doom about the future of Moorish Spain: 'Water and marble seem as one, so we know not which of the two flows. Do you not see how the water spills over the basin, but is hidden forthwith in the channels? It is a lover whose eyelids brim with tears; tears which then hide in fear of betrayal.'

I had wanted to travel to the Middle East this autumn to indulge my love of Islamic architecture, history and music, but the events of 11 September and a growing fear of flying changed my plans. All the cheap flights in the world couldn't persuade me that a holiday in the Arab world would be an entirely relaxing experience while George Bush and Osama bin Laden were intent on playing Crusaders and Saracens.

So I decided to travel across the surface of the earth, by boat from Plymouth to Santander, and then by train via Madrid to Granada. A plane may get you to southern Spain in a matter of hours, but travelling by train gives you a far better idea of the vastness of the country, from the lush green fields and forests of the North, through the bleak plains of La Mancha to the mountains of the Sierra Morena that mark the traditional boundary of Al Andalus.

Granada still has the feel of a Moorish city. All the more so as the old Arab quarter, the Albayzin, has begun to be resettled by immigrants from north Africa who have set up tea shops and restaurants in the narrow streets of the old casbah. Many of the old Moorish merchants' houses in the Albayzin have been restored as hotels, some with astonishing views of the Alhambra, and most of the city's churches were once mosques with the minarets converted into bell towers.

On a hot evening over sweet mint tea and pastries a visitor could be mistaken for thinking they were in a north African souk. But the great days of Granada were also its days of decadence, its rulers knowing it was only a matter of time before they were overrun by the Christian infidels.

If he had really wanted to revel in the past glory of Islamic Spain, Washington Irving's 'turbaned Moor' should have travelled north to Cordoba, the capital of Muslim Andalucia from 756 to 1031, which finally fell to the Christians in the thirteenth century.

At the height of its power, Cordoba was a serious rival to the other great centres of the Muslim empire, Baghdad and Damascus. The city became a magnet for artists and musicians from across the Arab world, including the great Baghdad lute player and singer Ziryab, who brought new skills in hairdressing, fashion and cookery to Europe, including, it is said, the convention of eating in courses with sweet food following savoury.

During this period the city became a centre of Jewish and Arabic poetry, mainly devoted to the subject of love, although wine was also a popular topic. And Cordoba was the birthplace of two of the greatest figures of medieval thought: Averroes and Maimonides, who introduced Aristotelian philosophy into Islamic and Jewish thought respectively.

Cordoba's 'Mezquita' remains the most potent symbol of the grandeur and tragedy of 'Al Andalus'. The signs may call it Cordoba Cathedral but once inside the Mezquita, with its forest of red brick and white stone candy-striped arches, it is clear this was once one of the grandest mosques in the Islamic world. It doesn't feel like a Christian building at all.

The city's vast gothic cathedral, built directly into the centre of the even vaster mosque has never really persuaded anyone of its superiority over the Muslim edifice.

In Cordoba, as in Granada, it is possible to stay in restored ancient houses in narrow cobbled streets - this time in the Jewish quarter - where, with a little imagination, you might think 1492 (or 11 September) had never happened.

Right across southern Spain in the towns between Cordoba and the coast, the traces of Muslim Andalucia can be found if people are prepared to look. The ruined Arab castle on the hill overlooking the town of Antequera on the main road from Cordoba to the sea and the Moorish quarter of Ronda, just north of Marbella, are both within a morning's drive from the Costa del Sol. And the sunshine resorts themselves - Malaga, Marbella and Estepona - each have their own remnants of Islamic rule in the form of ruined castles, although tourists rarely take the trouble to find them.

But it is difficult not to be drawn back to Granada, the last great city of Spanish Islam and its most romantic. One evening at a concert hall 100 yards from the walls of the Alhambra, as I listened to a group of Arabic musicians playing songs from the time of the Nasrids, I was struck by the absurdity of the notion that we are engaged in just the latest stage of the eternal clash between Christian and Muslim civilisations. Even to an untrained ear, the origins of Spanish flamenco are unmistakable in the intricate improvisations of the Oud (the Arabic forerunner of the guitar) accompanying the high, mournful singing of poems of love. In this part of the world, the two civilisations meshed with Jewish and gypsy elements to form one of the richest cultures Europe has ever known. Even the Inquisition could never fully excise this mongrel culture from the southern Spanish psyche, which survives not just in the flamenco, but also in the love of poetry, the romantic folk tales of buried Moorish treasure and the chivalric stories so beloved of Cervantes and his hero Don Quixote.

One story above all captures the romance and pain of Moorish Andalucia: that of Muhammed XI, the last Muslim ruler of Granada. Known as Abu Abdallah to his subjects - later corrupted to Boabdil by the Spanish - he presided over the final decade of civil war and strife in a shrivelled empire that once stretched to Salamanca in the North, Lisbon in the West and Valencia in the East. In one final humiliation in 1492, he was forced to surrender the Alhambra itself to Ferdinand and Isabella, and thus sign away the final vestige of Muslim Spain.

Boabdil was first imprisoned and then granted control of the mountainous Alpujarras region south of Granada to live out his days in internal exile, but his heart was broken and he fled to North Africa.

His mother was less generous to Boabdil than his Catholic conquerors, and is alleged to have said: 'Weep like a woman, you who have not defended your kingdom like a man.'

As he left, Boabdil took one final glance back at his beloved Alhambra palace and heaved a terrible sigh at the thought of the lost glory of the European empire of the Moors. El Suspiro del Moro, The Moor's Last Sigh, has since come to signify the end of Muslim dreams of a European empire and the beginning of the military and economic dominance of the Christian West.

The Alhambra is a reminder that, at one time, Islam was associated in the European mind with luxury, forbidden desires and permissive sexual morality rather than terror, suicide and the denial of all pleasures of the flesh. This makes it the perfect place to visit at a time when the Western world is being swamped with images of the humourless, puritanical face of modern Islam.

Factfile

Getting there: Brittany Ferries (0870 536 0360) has twice weekly sailings from Plymouth to Santander throughout the summer. Sailings begin again on March 13. A return based on two foot passengers sharing a two-berth cabin costs from £292 for a 10-day saver fare. Spanish national rail company RENFE are at www.renfe.es or call 020 7499 9100

Accommodation: Hotel Carmen de Santa Ines, Placeta de Porras, Calle San Juan de los Reyes 15, Granada (00 34 958 226380). Doubles £60-£115. Exquisite Moorish house in the Arab quarter of Granada with some rooms overlooking the Alhambra. Hotel Albucasis, Calle Buen Pastor 11, Cordoba (00 34 957 478 625). Doubles £35. Functional hotel with simple rooms in the Jewish quarter of Cordoba. Kempinski Resort Hotel, Playa el Padron, Estepona (0034 95 280 9500). Doubles from £115. Luxury resort on the Costa del Sol built in 1999 in neo Moorish style

Sightseeing: The Alhambra must be booked in advance to avoid a long wait. Call 00 34 902 22 44 60 or book through any branch of Banco BBV in Spain. Adult entrance fee 1,000 ptas (£4) plus a small booking fee