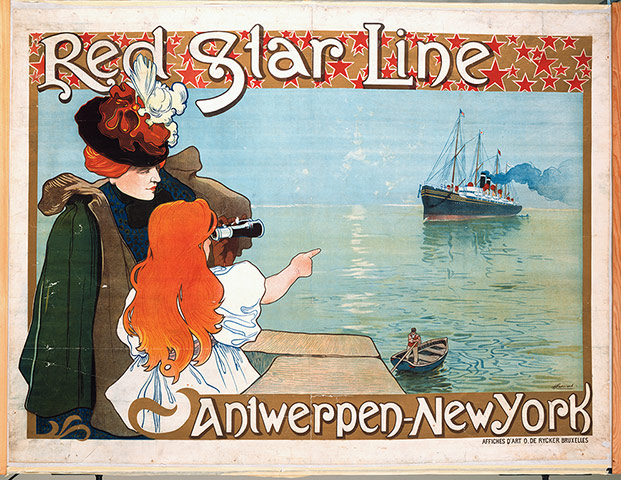

The Red Star Line was founded in 1872 by Philadelphia shipbrokers and Antwerp shipowners. Its first ship, the Vaderland, left on its maiden voyage from Antwerp to Philadelphia on 19 January 1873. During the line’s heyday, two ships left for North America every week. It operated until 1934, and ferried about 2.5 million passengers across the Atlantic. At the turn of the century, transatlantic ocean travel was a novel and glamorous experience, as this art nouveau poster by Henri Cassiers suggests. The Red Star Line Museum opened in Antwerp on 28 September 2013. Photograph: Red Star Line Museum

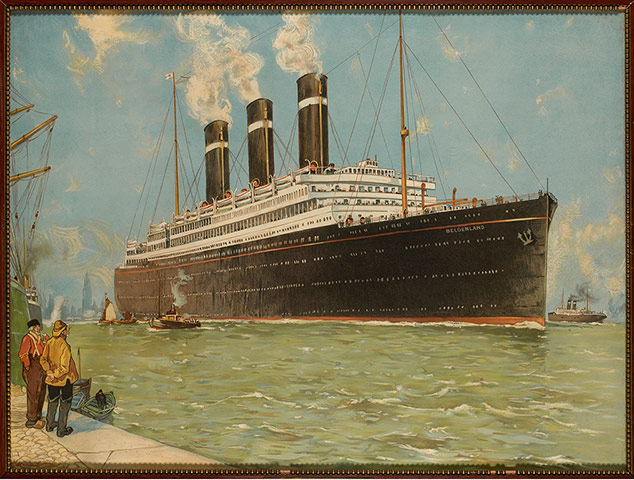

The Red Star Line hailed its vessels as miracles of technology. Its flagship in the 1920s was the luxurious Belgenland II. Built in Belfast and originally commissioned in 1917 as a British troop ship, it was refitted as an ocean cruiser. It was 204 metres long, weighed 27,000 tonnes and could carry 2,700 passengers. Photograph: Red Star Line Museum

Sightseers and bathers watch the ocean liner as it emerges from the Scheldt river. It was eventually scrapped in Bo’ness, Scotland, in 1936. Photograph: Red Star Line Museum

According to historians, about 30 million Americans can trace their roots to these red-brick buildings, once the Red Star Line’s staging halls on the Rhine quay in Antwerp. The renovated sheds now house the Red Star Line Museum, which mirrors the Ellis Island Immigration Museum in New York where many of the passengers disembarked. Photograph: Red Star Line Museum

The original Red Star Line waterfront complex has been transformed into an interactive museum. A key addition is a viewing tower shaped like a ship's funnel. Photograph: Red Star Line Museum

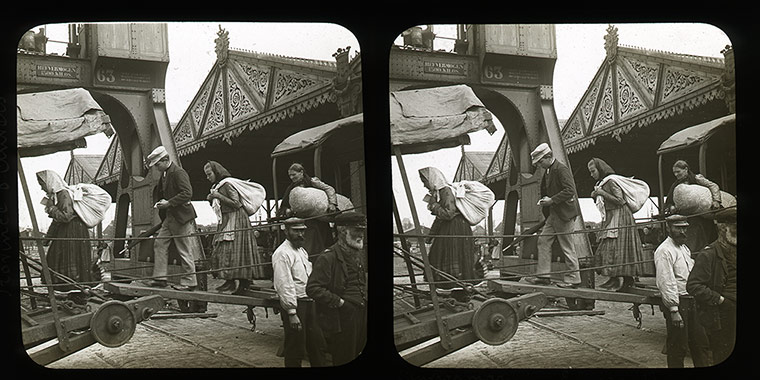

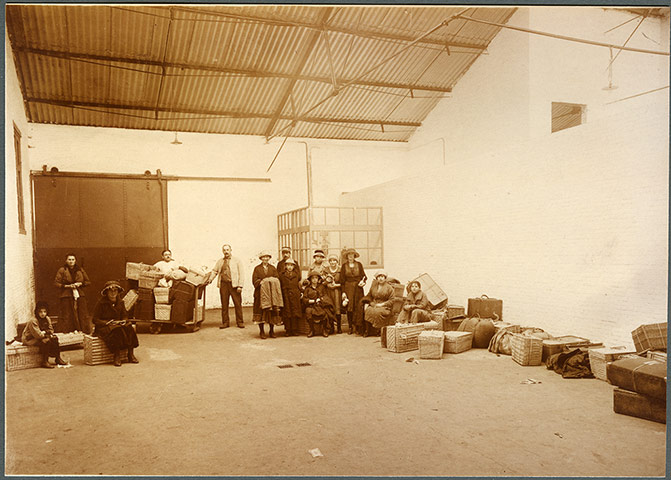

Many passengers were Jews fleeing the Nazi regime and the Russian pogroms of earlier eras, all seeking a better life across the ocean. After a long, hazardous journey across Europe, many would often arrive in Antwerp with just a sack of belongings on their backs. Photograph: Red Star Line Museum

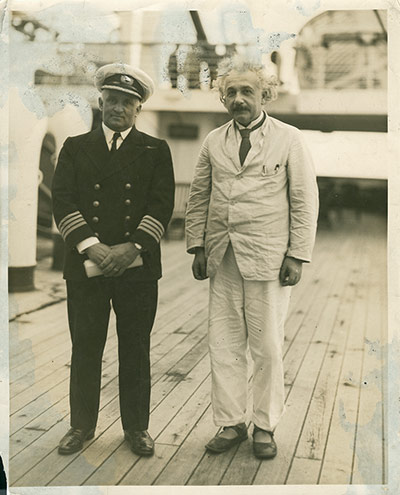

The physicist was a regular on the Red Star Line, travelling between Berlin and the US. He was on the Belgenland II, heading from New York to Antwerp in 1933, when he heard that the Nazis had come to power in Germany. The resignation letter he wrote to the Prussian Academy of Sciences while on the ship – on Red Star Line stationery – is on display at the museum. In October 1933, after a few months in Antwerp, he made his final departure to America from Southampton on the Westernland.

Photograph: Courtesy of the Red Star Line Museum Photograph: Red Star Line Museum

Another famous Red Star migrant was the composer Irving Berlin, author of White Christmas and There’s No Business Like Showbusiness. Born in Tolochin, in modern-day Belarus, he fled the Russian pogroms of 1893 with his family, landing in New York aged just five. His piano has been donated to the museum. Photograph: Red Star Line Museum

Before being allowed to travel, third-class passengers had to undergo rigorous health checks. The rules were strictly enforced, as anyone refused entry at Ellis Island would be sent back at the expense of the shipping line. In this picture, a nervous-looking group wait inside the Red Star Line hall. This part of the shed has been returned to its original state and is now a key part of the museum. Photograph: Red Star Line Museum

Sonia Pressman Fuentes, now 85, fled Berlin with her parents and 19-year-old brother after the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933. Here she is pictured in Central Park in 2013, beside a photograph of her with her father shortly after she arrived in New York in 1934, aged five. She became a lawyer and helped found the National Organisation for Women (Now) with Betty Friedan. “It’s very emotional to come to Antwerp and see all this,” she told the Guardian. “I’m alive today because of that voyage.”

Photograph: Courtesy of the Red Star Line Museum Photograph: Red Star Line Museum

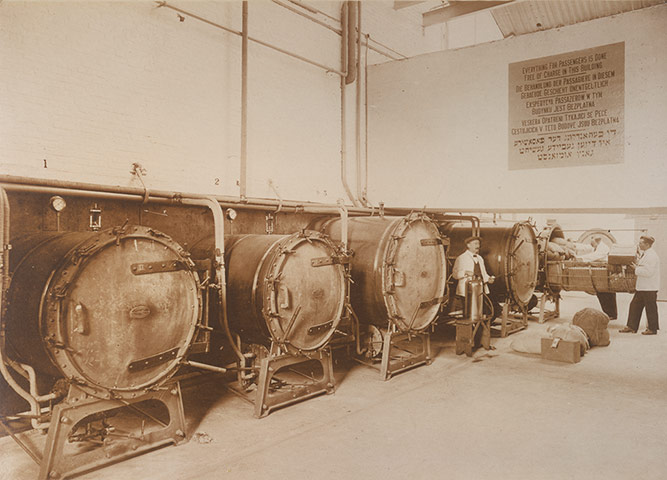

Worried that the newcomers would bring in infectious diseases such as cholera, typhoid fever and trachoma, the American authorities insisted on strict hygienic procedures. Men and women would take an hour-long shower with hot vinegar and benzene, to be cleaned and purged of lice. At the same time, their luggage was disinfected in autoclaves (large steam sterilising machines). Photograph: Red Star Line Museum

This image of an unnamed girl with a ticket inspired one of the museum’s campaigns, entitled Do you know this girl?, to discover the identities of passengers and to bring them to life. Photograph: Red Star Line Museum

Most travellers were emigrants with third-class tickets. For them, the passage to America was no pleasure trip: they were kept at the bottom of the ship, packed tightly together in large dormitories with hundreds of beds. If the weather obliged, they would be allowed on deck to escape their stuffy conditions. Photograph: Red Star Line Museum

The first waves of immigrants slowed after the turn of the century, and when the Belgenland II was launched in 1923, the 10-day Atlantic voyage was rebranded as a cruise, pitched at wealthy American and Europeans. Ben Bernie’s Music was one of the bands that performed on steamers. Photograph: Red Star Line Museum

Ocean steamers such as the Lapland (built in Belfast in 1908) were small, contained worlds, with similar social divides to on land. First-class passengers had their own cabins, enjoying opulent meals and entertainment in the evening, including dances. Belgenland II even had a swimming pool, complete with sand from the beach at Ostend. Photograph: Red Star Line Museum